極限是進入微積分的第一步,它解釋了該學科的複雜性。它用於定義導數和積分的過程。它還在其他情況下被用來直觀地展示“逼近”的過程。

極限是任何數學家手中的強大工具之一。我們將對極限進行一種方法的解釋。因為數學的出現僅僅是由於方法……還記得嗎?!

我們將極限表示為以下形式

lim x → a f ( x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to a}f(x)} 這讀作“當 x {\displaystyle x} a {\displaystyle a} f {\displaystyle f}

我們將在後面討論如何確定 f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} a {\displaystyle a}

假設我們感興趣的函式是 f ( x ) = x 2 {\displaystyle f(x)=x^{2}} x {\displaystyle x} 2 {\displaystyle 2}

lim x → 2 x 2 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}x^{2}} 評估此極限的一種方法是選擇接近 2 的值,計算每個值的 f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)}

x {\displaystyle x} 1.7

1.8

1.9

1.95

1.99

1.999

f ( x ) = x 2 {\displaystyle f(x)=x^{2}} 2.89

3.24

3.61

3.8025

3.9601

3.996001

上面的表格是自下而上的情況。

x {\displaystyle x} 2.3

2.2

2.1

2.05

2.01

2.001

f ( x ) = x 2 {\displaystyle f(x)=x^{2}} 5.29

4.84

4.41

4.2025

4.0401

4.004001

上面的表格是自上而下的情況。

從表格中可以看出,當 x {\displaystyle x} f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} x {\displaystyle x} x 2 {\displaystyle x^{2}} x {\displaystyle x}

lim x → 2 x 2 = 4 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}x^{2}=4} 我們也可以直接將 2 代入 x 2 {\displaystyle x^{2}} ( 2 ) 2 = 4 {\displaystyle (2)^{2}=4}

現在讓我們來看另一個例子。假設我們對函式 f ( x ) = 1 x − 2 {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x-2}}} x {\displaystyle x}

lim x → 2 1 x − 2 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\frac {1}{x-2}}} 與之前一樣,我們可以計算函式值,當 x {\displaystyle x}

x {\displaystyle x} 1.7

1.8

1.9

1.95

1.99

1.999

f ( x ) = 1 x − 2 {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x-2}}} -3.333

-5

-10

-20

-100

-1000

以下是從上方趨近:

x {\displaystyle x} 2.3

2.2

2.1

2.05

2.01

2.001

f ( x ) = 1 x − 2 {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x-2}}} 3.333

5

10

20

100

1000

在這種情況下,函式似乎沒有隨著 x {\displaystyle x}

請注意,我們不能像第一個例子那樣,直接將 2 代入 1 x − 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{x-2}}}

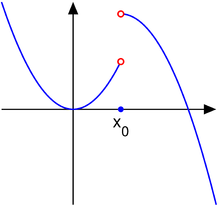

這兩個例子看起來可能很瑣碎,但請考慮以下函式:

f ( x ) = x 2 ( x − 2 ) x − 2 {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {x^{2}(x-2)}{x-2}}} 此函式與以下函式相同:

f ( x ) = { x 2 if x ≠ 2 undefined if x = 2 {\displaystyle f(x)=\left\{{\begin{matrix}x^{2}&{\text{if }}x\neq 2\\{\mbox{undefined}}&{\text{if }}x=2\end{matrix}}\right.} 請注意,這些函式實際上是完全相同的;不僅僅是“幾乎相同”,而是根據函式定義,完全相同;它們對每個輸入都給出完全相同的輸出。

在初等代數中,一種典型的方法是簡單地說,我們可以取消 ( x − 2 ) {\displaystyle (x-2)} f ( x ) = x 2 {\displaystyle f(x)=x^{2}} x = 2 {\displaystyle x=2} x = 2 {\displaystyle x=2} 0 = 1 {\displaystyle 0=1} 數學謬誤 § 所有數字都等於所有其他數字 的完整示例)。即使沒有微積分,我們也可以透過以下說法來避免這種錯誤。

f ( x ) = x 2 ( x − 2 ) x − 2 = x 2 when x ≠ 2 {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {x^{2}(x-2)}{x-2}}=x^{2}{\text{ when }}x\neq 2} 在微積分中,我們可以引入一種更直觀且更正確的方式來看待這種型別的函式。我們希望能夠說,儘管函式在 x = 2 {\displaystyle x=2} f ( 1.99999 ) = 3.99996 {\displaystyle f(1.99999)=3.99996}

由於極限的精確定義有點技術性,所以從非正式定義開始會更容易;我們稍後會解釋正式定義。

我們假設函式 f {\displaystyle f} x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} x = c {\displaystyle x=c}

注意,極限的定義與當 x = c {\displaystyle x=c} f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)}

極限也可以理解為: x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c} f ( x ) = 1 x {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x}}} 0 {\displaystyle 0} 0 {\displaystyle 0}

現在我們已經非正式地定義了什麼是極限,接下來我們將列出一些對處理和計算極限很有用的規則。一旦我們正式定義了函式極限的基本概念,你就可以證明所有這些規則。

首先,**常數規則**指出,如果 f ( x ) = b {\displaystyle f(x)=b} f {\displaystyle f} x {\displaystyle x} x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} b {\displaystyle b}

**示例**: lim x → 6 5 = 5 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 6}5=5} 其次,**恆等式規則**指出,如果 f ( x ) = x {\displaystyle f(x)=x} f {\displaystyle f} f {\displaystyle f} x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c}

極限的恆等式規則

如果 c {\displaystyle c} lim x → c x = c {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}x=c}

**例子**: lim x → 6 x = 6 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 6}x=6} 接下來的幾條規則告訴我們,在已知一些極限值的情況下,如何計算其他極限。

請注意,在最後一個規則中,我們需要要求 M {\displaystyle M}

這些規則被稱為 **恆等式**;它們是極限的標量積、和、差、積和商規則。(標量是常數,當您將函式乘以常數時,我們說您正在執行 **標量乘法**。)

利用這些規則,我們可以推匯出另一個規則。即,多次使用乘積規則,我們得到

lim x → c f ( x ) n = ( lim x → c f ( x ) ) n = L n {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}f(x)^{n}=\left(\lim _{x\to c}f(x)\right)^{n}=L^{n}} n {\displaystyle n} 這被稱為 **冪規則**。

因此,我們可以肯定地說,所有多項式函式的極限都可以推匯出滿足恆等式規則的幾個極限,因此更容易計算。

示例 1 求極限 lim x → 2 4 x 3 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}4x^{3}}

我們需要簡化問題,因為我們沒有關於這個表示式本身的規則。我們從上面的恆等式規則知道 lim x → 2 x = 2 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}x=2} lim x → 2 x 3 = ( lim x → 2 x ) 3 = 2 3 = 8 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}x^{3}=\left(\lim _{x\to 2}x\right)^{3}=2^{3}=8} lim x → 2 4 x 3 = 4 ⋅ lim x → 2 x 3 = 4 ⋅ 8 = 32 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}4x^{3}=4\cdot \lim _{x\to 2}x^{3}=4\cdot 8=32}

◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare }

示例 2 求極限 lim x → 2 [ 4 x 3 + 5 x + 7 ] {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\Big [}4x^{3}+5x+7{\Big ]}}

非正式地,我們將表示式再次拆分成它的組成部分。如上所述, lim x → 2 4 x 3 = 32 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}4x^{3}=32}

此外, lim x → 2 5 x = 5 ⋅ lim x → 2 x = 5 ⋅ 2 = 10 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}5x=5\cdot \lim _{x\to 2}x=5\cdot 2=10} lim x → 2 7 = 7 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}7=7}

lim x → 2 [ 4 x 3 + 5 x + 7 ] = lim x → 2 4 x 3 + lim x → 2 5 x + lim x → 2 7 = 32 + 10 + 7 = 49 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\Big [}4x^{3}+5x+7{\Big ]}=\lim _{x\to 2}4x^{3}+\lim _{x\to 2}5x+\lim _{x\to 2}7=32+10+7=49} ◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare } 例 3 求極限 lim x → 2 4 x 3 + 5 x + 7 ( x − 4 ) ( x + 10 ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\frac {4x^{3}+5x+7}{(x-4)(x+10)}}}

根據前面的例子,分子極限為 lim x → 2 [ 4 x 3 + 5 x + 7 ] = 49 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\Big [}4x^{3}+5x+7{\Big ]}=49}

lim x → 2 ( x − 4 ) ( x + 10 ) = lim x → 2 [ x − 4 ] ⋅ lim x → 2 [ x + 10 ] = ( 2 − 4 ) ( 2 + 10 ) = − 24 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}(x-4)(x+10)=\lim _{x\to 2}{\big [}x-4{\big ]}\cdot \lim _{x\to 2}{\big [}x+10{\big ]}=(2-4)(2+10)=-24} 由於分母極限不等於零,我們可以進行除法運算。結果為

lim x → 2 4 x 3 + 5 x + 7 ( x − 4 ) ( x + 10 ) = − 49 24 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\frac {4x^{3}+5x+7}{(x-4)(x+10)}}=-{\frac {49}{24}}} ◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare } 例 4 求極限 lim x → 4 x 4 − 16 x + 7 4 x − 5 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 4}{\frac {x^{4}-16x+7}{4x-5}}}

我們用與上一組示例相同的過程;

lim x → 4 x 4 − 16 x + 7 4 x − 5 = lim x → 4 [ x 4 − 16 x + 7 ] lim x → 4 [ 4 x − 5 ] = lim x → 4 x 4 − lim x → 4 16 x + lim x → 4 7 lim x → 4 4 x − lim x → 4 5 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 4}{\frac {x^{4}-16x+7}{4x-5}}={\frac {\lim \limits _{x\to 4}{\Big [}x^{4}-16x+7{\Big ]}}{\lim \limits _{x\to 4}{\Big [}4x-5{\Big ]}}}={\frac {\lim \limits _{x\to 4}x^{4}-\lim \limits _{x\to 4}16x+\lim \limits _{x\to 4}7}{\lim \limits _{x\to 4}4x-\lim \limits _{x\to 4}5}}} 我們可以計算出這些值; lim x → 4 ( x 4 ) = 256 , lim x → 4 ( 16 x ) = 64 , lim x → 4 ( 7 ) = 7 , lim x → 4 ( 4 x ) = 16 , lim x → 4 ( 5 ) = 5. {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 4}(x^{4})=256\ ,\ \lim _{x\to 4}(16x)=64\ ,\ \lim _{x\to 4}(7)=7\ ,\ \lim _{x\to 4}(4x)=16\ ,\ \lim _{x\to 4}(5)=5.} 199 11 {\displaystyle {\frac {199}{11}}}

◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare } 示例 5 求極限 lim x → 2 x 2 − 3 x + 2 x − 2 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\frac {x^{2}-3x+2}{x-2}}}

在這個例子中,直接計算結果會導致除以 0。雖然你可以透過實驗確定答案,但也可以使用數學方法來解決。

首先,分子是一個可以因式分解的多項式: lim x → 2 ( x − 2 ) ( x − 1 ) x − 2 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\frac {(x-2)(x-1)}{x-2}}}

現在,我們可以用 ( x − 2 ) {\displaystyle (x-2)} lim x → 2 ( x − 1 ) = ( 2 − 1 ) = 1 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}(x-1)=(2-1)=1}

請記住,極限是一種確定函式逼近值的方法,而不是函式本身的值。因此,雖然函式在 x = 2 {\displaystyle x=2} x → 2 {\displaystyle x\rightarrow 2} 1 {\displaystyle 1}

◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare } 示例 6 求極限 lim x → 0 [ 1 − cos ( x ) x ] {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {1-\cos(x)}{x}}\right]}

為了計算這個看似複雜的極限,我們需要回憶一些正弦和餘弦恆等式(參見第 1.3 章)。我們還需要用到兩個新的事實。首先,如果 f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} a {\displaystyle a} lim x → a f ( x ) = f ( a ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to a}f(x)=f(a)}

其次, lim x → 0 sin ( x ) x = 1 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {\sin(x)}{x}}=1} 夾逼定理 證明。注意洛必達法則不能用來計算這個極限,因為它會導致迴圈推理,

也就是說,求 sin x {\displaystyle \sin x}

方法 1(在學習洛必達法則之前)

為了計算極限,認識到 1 − cos ( x ) {\displaystyle 1-\cos(x)} 1 + cos ( x ) {\displaystyle 1+\cos(x)} 1 − cos 2 ( x ) {\displaystyle 1-\cos ^{2}(x)} sin 2 ( x ) {\displaystyle \sin ^{2}(x)} 1 + cos ( x ) {\displaystyle 1+\cos(x)}

lim x → 0 [ 1 − cos ( x ) x ] {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {1-\cos(x)}{x}}\right]} = lim x → 0 [ 1 − cos ( x ) x ⋅ 1 1 ] {\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {1-\cos(x)}{x}}\cdot {\frac {1}{1}}\right]}

= lim x → 0 [ 1 − cos ( x ) x ⋅ 1 + cos ( x ) 1 + cos ( x ) ] {\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {1-\cos(x)}{x}}\cdot {\frac {1+\cos(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]}

= lim x → 0 ( 1 − cos ( x ) ) ( 1 + cos ( x ) ) x ( 1 + cos ( x ) ) {\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {{\big (}1-\cos(x){\big )}{\big (}1+\cos(x){\big )}}{x{\big (}1+\cos(x){\big )}}}}

= lim x → 0 1 − cos 2 ( x ) x ( 1 + cos ( x ) ) {\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1-\cos ^{2}(x)}{x{\big (}1+\cos(x){\big )}}}}

= lim x → 0 sin 2 ( x ) x ( 1 + cos ( x ) ) {\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {\sin ^{2}(x)}{x{\big (}1+\cos(x){\big )}}}}

= lim x → 0 [ sin ( x ) x ⋅ sin ( x ) 1 + cos ( x ) ] {\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{x}}\cdot {\frac {\sin(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]}

下一步是根據乘積法則將它分解成 lim x → 0 [ sin ( x ) x ] ⋅ lim x → 0 [ sin ( x ) 1 + cos ( x ) ] {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{x}}\right]\cdot \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]} lim x → 0 [ sin ( x ) x ] = 1 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{x}}\right]=1}

接下來, lim x → 0 [ sin ( x ) 1 + cos ( x ) ] = lim x → 0 [ sin ( x ) ] lim x → 0 [ 1 + cos ( x ) ] = 0 1 + cos ( 0 ) = 0 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]={\frac {\lim \limits _{x\to 0}{\big [}\sin(x){\big ]}}{\lim \limits _{x\to 0}{\big [}1+\cos(x){\big ]}}}={\frac {0}{1+\cos(0)}}=0}

因此,將這兩個結果相乘,我們得到 0。

◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare }

注意,我們也不能使用洛必達法則來計算這個極限,因為它會導致迴圈論證。

現在我們將介紹一個非常有用的結果,儘管我們還無法證明它。只要該有理函式在 c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c}

我們已經學習了三角函式的這一特性,因此我們發現,只要多項式、有理函式或三角函式定義在某點,就能很容易地求出它們的極限。事實上,即使對於這些函式的組合,這也適用;因此,例如, lim x → 1 [ sin ( x 2 ) + 4 cos 3 ( 3 x − 1 ) ] = sin ( 1 2 ) + 4 cos 3 ( 3 ⋅ 1 − 1 ) = sin 1 + 4 cos 3 2 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 1}{\bigg [}\sin(x^{2})+4\cos ^{3}(3x-1){\bigg ]}=\sin(1^{2})+4\cos ^{3}(3\cdot 1-1)=\sin 1+4\cos ^{3}2}

顯示 f {\displaystyle f} g {\displaystyle g} h {\displaystyle h} 夾擠定理在微積分中非常重要,通常用於透過與兩個已知極限的函式進行比較來求解函式的極限。

它被稱為夾逼定理,因為它指的是一個函式 f {\displaystyle f} g {\displaystyle g} h {\displaystyle h} L {\displaystyle L} f {\displaystyle f} g {\displaystyle g} h {\displaystyle h} f {\displaystyle f} L {\displaystyle L}

更精確地說

x ⋅ sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle x\cdot \sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)} − 0.5 < x < 0.5 {\displaystyle -0.5<x<0.5} 示例 :計算 lim x → 0 x ⋅ sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}x\cdot \sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)}

由於我們知道

− 1 ≤ sin ( 1 x ) ≤ 1 {\displaystyle -1\leq \sin({\frac {1}{x}})\leq 1}

將 x {\displaystyle x}

− | x | ≤ x sin ( 1 x ) ≤ | x | {\displaystyle -|x|\leq x\sin({\frac {1}{x}})\leq |x|}

現在我們應用夾逼定理

lim x → 0 − | x | ≤ lim x → 0 x sin ( 1 x ) ≤ lim x → 0 | x | {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}-|x|\leq \lim _{x\to 0}x\sin({\frac {1}{x}})\leq \lim _{x\to 0}|x|}

由於 lim x → 0 − | x | = lim x → 0 | x | = 0 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}-|x|=\lim _{x\to 0}|x|=0}

lim x → 0 x ⋅ sin ( 1 x ) = 0 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}x\cdot \sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)=0}

◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare }

現在,我們將討論在實踐中如何求極限。首先,如果函式可以由有理函式、三角函式、對數函式或指數函式構成,那麼如果一個數 c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c}

lim x → c f ( x ) = f ( c ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}f(x)=f(c)} f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} c ∈ {\displaystyle c\in } f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)}

如果 c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c} lim x → 0 x x {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {x}{x}}}

在這種情況下,為了找到 lim x → c f ( x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}f(x)} g ( x ) {\displaystyle g(x)} f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} c {\displaystyle c} f {\displaystyle f} g {\displaystyle g} f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c} c {\displaystyle c} lim x → c g ( x ) = L {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}g(x)=L} lim x → c f ( x ) = L {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}f(x)=L} g {\displaystyle g} c {\displaystyle c} g {\displaystyle g} c {\displaystyle c} lim x → c f ( x ) = g ( c ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}f(x)=g(c)}

在我們這個例子中,這很簡單;把 x {\displaystyle x} g ( x ) = 1 {\displaystyle g(x)=1} f ( x ) = x x {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {x}{x}}} lim x → 0 x x = lim x → 0 1 = 1 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {x}{x}}=\lim _{x\to 0}1=1}

請注意,極限可能根本不存在(DNE 表示“不存在”)。這可以透過多種方式發生。

“間隙”

f ( x ) = x 2 − 16 {\displaystyle f(x)={\sqrt {x^{2}-16}}} f ( x ) = x 2 − 16 {\displaystyle f(x)={\sqrt {x^{2}-16}}} lim x → c f ( x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}f(x)} − 4 ≤ c ≤ 4 {\displaystyle -4\leq c\leq 4} c = − 4 {\displaystyle c=-4} c = 4 {\displaystyle c=4} 左右 兩側接近。還要注意,在圖形上的完全孤立的點上不存在極限。 跳躍間斷。 “跳躍” 如果圖形突然跳到另一個水平,則跳躍點沒有極限。例如,設 f ( x ) {\displaystyle f(x)} ≤ x {\displaystyle \leq x} c {\displaystyle c} x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} f ( x ) = c {\displaystyle f(x)=c} x {\displaystyle x} c {\displaystyle c} f ( x ) = c − 1 {\displaystyle f(x)=c-1} lim x → c f ( x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}f(x)} 在區間 [ − 2 , 2 ] {\displaystyle [-2,2]} 1 x 2 {\displaystyle {\frac {1}{x^{2}}}} 垂直漸近線

在 f ( x ) = 1 x 2 {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x^{2}}}}

圖形隨著接近 0 而變得任意高,因此不存在極限。(在這種情況下,我們有時說極限是無限的;參見下一節。) 在區間 ( 0 , 1 π ] {\displaystyle (0,{\tfrac {1}{\pi }}]} sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle \sin({\tfrac {1}{x}})} 無限振盪

接下來的兩個可能難以視覺化。在這裡,我們指的是圖形不斷地上升到水平線之上並下降到水平線之下。事實上,隨著你接近某個 x {\displaystyle x} x {\displaystyle x}

振盪的使用自然會讓人聯想到三角函式。一個三角函式的例子是,它在 x {\displaystyle x}

f ( x ) = sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle f(x)=\sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)} As x {\displaystyle x} − 1 {\displaystyle -1} sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle \sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)} x {\displaystyle x} x = k π {\displaystyle x=k\pi } k {\displaystyle k} k {\displaystyle k} sin ( x ) {\displaystyle \sin(x)} − 1 {\displaystyle -1} sin ( 1 x ) = 0 {\displaystyle \sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)=0} x = 1 k π {\displaystyle x={\tfrac {1}{k\pi }}} 1 k π {\displaystyle {\tfrac {1}{k\pi }}} 1 ( k + 1 ) π {\displaystyle {\tfrac {1}{(k+1)\pi }}} sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle \sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)} − 1 {\displaystyle -1} 1 / π {\displaystyle 1/\pi } x {\displaystyle x} 1 π {\displaystyle {\tfrac {1}{\pi }}} x {\displaystyle x} x {\displaystyle x} sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle \sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)} lim x → 0 sin ( 1 x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\sin \left({\tfrac {1}{x}}\right)} 正式確定極限是否存在的方法是找出從下方和上方逼近時極限值是否相同(參見本章開頭)。從下方逼近(遞增順序)的極限記號為

lim x → c − f ( x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c^{-}}f(x)} c {\displaystyle c}

從上方逼近(遞減順序)的極限記號為

lim x → c + f ( x ) {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c^{+}}f(x)} c {\displaystyle c}

例如,讓我們求當 x {\displaystyle x} 0 {\displaystyle 0} f ( x ) = 1 x {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x}}} lim x → 0 − 1 x {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0^{-}}{\frac {1}{x}}} lim x → 0 + 1 x {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0^{+}}{\frac {1}{x}}}

回想一下我們之前嘗試直觀感受極限時製作的表格。我們可以利用它來幫助我們。但是,如果對倒數函式足夠熟悉,我們可以透過想象函式的影像來簡單地確定這兩個值。下表是在 x {\displaystyle x}

x {\displaystyle x} -0.3

-0.2

-0.1

-0.05

-0.01

-0.001

f ( x ) = 1 x {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x}}} -3.333

-5

-10

-20

-100

-1000

因此,我們發現當 x {\displaystyle x} 0 {\displaystyle 0}

lim x → 0 − 1 x = − ∞ {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0^{-}}{\frac {1}{x}}=-\infty }

現在讓我們談談從上方逼近的情況。

x {\displaystyle x} 0.3

0.2

0.1

0.05

0.01

0.001

f ( x ) = 1 x {\displaystyle f(x)={\frac {1}{x}}} 3.333

5

10

20

100

1000

我們發現 lim x → 0 + 1 x = ∞ {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0^{+}}{\frac {1}{x}}=\infty }

◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare }

確定極限是否存在的方法比較直觀。只要練習幾次,就能熟悉這個過程。

讓我們使用同一個例子:求 lim x → 0 1 x {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1}{x}}}

由於我們已經發現 lim x → 0 − 1 x = − ∞ {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0^{-}}{\frac {1}{x}}=-\infty } lim x → 0 + 1 x = ∞ {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0^{+}}{\frac {1}{x}}=\infty }

lim x → 0 − 1 x ≠ lim x → 0 + 1 x {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0^{-}}{\frac {1}{x}}\neq \lim _{x\to 0^{+}}{\frac {1}{x}}}

我們可以說 lim x → 0 1 x {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1}{x}}}

◼ {\displaystyle \blacksquare }

現在考慮函式

g ( x ) = 1 x 2 {\displaystyle g(x)={\frac {1}{x^{2}}}} 當 x {\displaystyle x} g ( 0 ) {\displaystyle g(0)}

請注意,我們可以透過選擇一個足夠小的 x {\displaystyle x} x ≠ 0 {\displaystyle x\neq 0} g ( x ) {\displaystyle g(x)} g ( x ) {\displaystyle g(x)} 10 12 {\displaystyle 10^{12}} x {\displaystyle x} 10 − 6 {\displaystyle 10^{-6}} lim x → 0 1 x 2 {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1}{x^{2}}}}

然而,我們確實知道當 x {\displaystyle x} g ( x ) {\displaystyle g(x)} x {\displaystyle x} g ( x ) {\displaystyle g(x)}

lim x → 0 g ( x ) = lim x → 0 1 x 2 = ∞ {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}g(x)=\lim _{x\to 0}{\frac {1}{x^{2}}}=\infty } 請注意,在 0 {\displaystyle 0} ∞ {\displaystyle \infty }

第二個定義的一個例子是 ** lim x → 0 − 1 x 2 = − ∞ {\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}-{\frac {1}{x^{2}}}=-\infty }

為了理解極限概念的強大之處,讓我們考慮一輛行駛的汽車。假設我們有一輛汽車,其位置相對於時間是線性的 (也就是說,繪製位置與時間關係的圖形將顯示一條直線)。我們想要找到它的速度。這在代數中很容易做到;我們只需取斜率,那就是速度。

但不幸的是,現實世界中的事物並不總是沿著漂亮的直線運動。汽車會加速、減速,並且通常以難以計算其速度的方式運動。

現在我們真正想做的是找到某個時刻的速度 (瞬時速度)。問題是,為了找到速度,我們需要兩個點,而任何給定時間,我們只有一個點。當然,我們總能找到汽車在兩個時間點之間的平均速度,但我們想找到汽車在一個精確時刻的速度。

這就是微積分的基本技巧,它是本書兩個主要主題中的第一個。我們取兩個時間點之間的平均速度,然後讓這兩個時間點越來越接近。然後我們觀察這兩個時間點越來越接近時斜率的極限,並稱這個極限是單個時刻的斜率。

我們將在本書後面更深入地研究這個過程。然而,首先,我們需要更仔細地研究極限。

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}{\Big [}f(x)+g(x){\Big ]}=\lim _{x\to c}f(x)+\lim _{x\to c}g(x)=L+M}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/63558973f7dd0b0f40d8b5ec75c0069be55cbfd5)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}{\Big [}f(x)-g(x){\Big ]}=\lim _{x\to c}f(x)-\lim _{x\to c}g(x)=L-M}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2245bcbbf23e62d18e911d97fb3374f21029d253)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to c}{\Big [}f(x)\cdot g(x){\Big ]}=\lim _{x\to c}f(x)\cdot \lim _{x\to c}g(x)=L\cdot M}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8bb3a49fa4c6cf42d9198a0a3a589f0d37f801ef)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\Big [}4x^{3}+5x+7{\Big ]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b9aa0dd59f814b3b6360f3bf16731fe0ce310506)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\Big [}4x^{3}+5x+7{\Big ]}=\lim _{x\to 2}4x^{3}+\lim _{x\to 2}5x+\lim _{x\to 2}7=32+10+7=49}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/89f353a2c991ed44a76cbe15ec92e1a7cef64b59)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}{\Big [}4x^{3}+5x+7{\Big ]}=49}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/353024d0a21d472b9fcc214957ec24ba2bba2071)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 2}(x-4)(x+10)=\lim _{x\to 2}{\big [}x-4{\big ]}\cdot \lim _{x\to 2}{\big [}x+10{\big ]}=(2-4)(2+10)=-24}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/65c63b2f02d6f5fcce2f8d9f4a03197753b87877)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 4}{\frac {x^{4}-16x+7}{4x-5}}={\frac {\lim \limits _{x\to 4}{\Big [}x^{4}-16x+7{\Big ]}}{\lim \limits _{x\to 4}{\Big [}4x-5{\Big ]}}}={\frac {\lim \limits _{x\to 4}x^{4}-\lim \limits _{x\to 4}16x+\lim \limits _{x\to 4}7}{\lim \limits _{x\to 4}4x-\lim \limits _{x\to 4}5}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7642ef2f4b9658fcf3b321603072b3855871b00c)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {1-\cos(x)}{x}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/439aaecbbba70015d6ba2bc0dbbdb28af2a4c879)

![{\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {1-\cos(x)}{x}}\cdot {\frac {1}{1}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/004dae8cac61686c58224237354804a0103ebd9a)

![{\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {1-\cos(x)}{x}}\cdot {\frac {1+\cos(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b7224657c3fd7b37a16b7a5588b984dda8bc95b3)

![{\displaystyle =\lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{x}}\cdot {\frac {\sin(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d41ba3366a2096441341036c51d162bec854de87)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{x}}\right]\cdot \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/01925eba7f3f6d88a6cb8834c53788681d75b7a5)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{x}}\right]=1}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/160f1b5c8451bba4f762d0423a4ddf0b4c06b44f)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 0}\left[{\frac {\sin(x)}{1+\cos(x)}}\right]={\frac {\lim \limits _{x\to 0}{\big [}\sin(x){\big ]}}{\lim \limits _{x\to 0}{\big [}1+\cos(x){\big ]}}}={\frac {0}{1+\cos(0)}}=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3162bb4a9f849e9fce9bed16c245dd028f15052a)

![{\displaystyle \lim _{x\to 1}{\bigg [}\sin(x^{2})+4\cos ^{3}(3x-1){\bigg ]}=\sin(1^{2})+4\cos ^{3}(3\cdot 1-1)=\sin 1+4\cos ^{3}2}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/57ef4597d5d1294ea634e4d530898e083ed19734)

![{\displaystyle [-2,2]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f94b820404eca2a458cb2c7d8c24be85fffccf90)

![{\displaystyle (0,{\tfrac {1}{\pi }}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f41cc2319c9c4acc7cd957eb6a02fc6070fa869a)